In the next two installments in our series on lease fundamentals, “The ABCs of Commercial Real Estate Leases”, we’re going to address Rent and Additional Recoverable Expenses, an important topic considering Base Rent and Recoverable Expenses account for the lion’s share of revenue from commercial real estate properties. In this post, we’re going to discuss Gross and Net Leases and explain the main differences between the two. But first, some related terms that are helpful to know:

Base Rent

Also known as Minimum Rent. In a commercial lease, a tenant typically pays a fixed amount each month as “Base Rent” or “Minimum Rent.” Base Rent may be provided as a dollar per square foot amount, a monthly fixed dollar amount, or an annual fixed dollar amount.

Abatements

Abatement is the reduction or elimination of a continuing charge (including Base Rent, expense recoveries, percentage rent and/or any other cash consideration) required to be paid by a tenant under a lease for a specified period of time.

Additional Rent

Also referred to as Recoverable Expenses. Additional Rent is any financial obligation of the tenant payable to the landlord other than Base Rent. Additional Rent may include items such as operating expenses, taxes, percentage rent, CPI adjustments and late fees. Items of Additional Rent such as expense recoveries and taxes are typically based on a tenant’s Pro Rata Share of rented space in the building, property or complex (the “Defined Area”). Most other items of Additional Rent, such as percentage rent, CPI and Porters Wage adjustments, and late fees are independent of a tenant’s Pro Rata Share. Tenants are usually required to pay their pro rata share of some or all of the operating expenses and taxes associated with the landlord’s ownership and operation of the premises and building. Operating expenses may include any number of items, including taxes. If taxes are not included as an item of operating expenses, then they are typically paid separately.

Operating expenses commonly include:

- Utilities

- Insurance

- Maintenance and Repairs

- Janitorial Services and Supplies

- Security

- Landscaping/Snow Removal

- Management and Association Fees

- Amortization of Capital Improvements (with restrictions)

How A Landlord Determines Additional Rent/Recoverable Expenses

Annually, a landlord prepares a budget estimating what is expected to be spent during the upcoming year (calendar or fiscal) to operate and maintain the building. These expenses are tabulated and applied to each tenant according to the terms of the lease. After applying the terms of the lease against the budgeted expenses, the landlord will know how much needs to be collected from a tenant to cover that tenant’s share of the building expenses. These collections are usually made monthly as part of the tenant’s rent payment.

Within a short period of time from the end of each year, the landlord will determine what its actual operating expenses were for the past year. The landlord will take this final number and subtract from it the monthly payments (“deposits”) that the tenant has made toward these final expenses during the year. The result will either be a credit due to the tenant because final expenses were less than what was “deposited,” or, the tenant will owe an additional amount because the final expenses were higher than what was “deposited”.

This is a very simplistic explanation of the process and multiple variations exist to how a landlord and tenant handle their reimbursements, but generally, the basic mechanics are as outlined above.

Gross Leases vs Net Leases

A modified Gross Lease is one in which a tenant pays its share of operating expenses in excess of a certain base amount. That amount can be stated as a Base Year or as an Expense Stop.

For example:

- A tenant signs a lease that states it will pay its pro‐rata share of operating expenses in excess of those for calendar year 2022. If the tenant moves in on 05/01/22, it will not pay any operating expenses for the remainder of 2022. Once the landlord determines the final costs to operate the building for 2022, it will inform the tenant of that amount, which is the Base Year amount. Going forward, any operating expenses for subsequent years that exceed that dollar amount (the Base) will be due from the tenant.

- Assume it costs $5.00/sq. ft. to operate the building in 2022 (the Base Year), and it costs $5.25/sq. ft. to operate the building in 2023. Subtracting the Base Year amount from the current year amount results in the tenant paying $0.25/sq. ft. in 2022 as its share of operating expenses. If the costs to operate the building for 2023 are $4.95/sq. ft., the tenant will not owe anything to the Landlord for that year because the Base Year expenses exceed the current year expenses. Unless written otherwise in the lease, the landlord will not owe anything to the tenant for that year.

- The Base Year amount listed in the example above was $5.00/sq. ft. This is also known as an “Expense Stop.” A lease may state that the tenant will pay its pro‐rata share of operating expenses in excess of a certain dollar amount. That would be a lease with a specified Expense Stop.

A Net Lease is one in which the tenant begins paying operating expenses based upon the estimate for the year of commencement without any consideration for a Base or Expense Stop amount. That is, if the tenant is expected to move in on 5/1/22, the landlord will inform the tenant that operating expenses are expected to be $5.00/sq. ft. for 2022 and the tenant will begin paying that amount upon commencement. Each year thereafter, the tenant will pay the estimated amount for such year without subtraction of a Base amount.

The determination of whether a lease is written as “Gross” or “Net” is usually done based upon market traditions. That is, most leases in a particular city or region are all written the same way. This makes it easier for tenants and brokers to evaluate proposals and for landlords to administer the leases.

Variations of Gross and Net Leases

Variations of simple Gross and Net leases do exist:

- A “Full Gross” lease is one that does not account for operating expenses. The tenant will pay a base rental (with or without fixed increases) over the term, but will not pay expense recoveries. The landlord should have factored the estimated operating expenses for the term of the lease into the base rent, and assumes any risk in the event these estimates are incorrect.

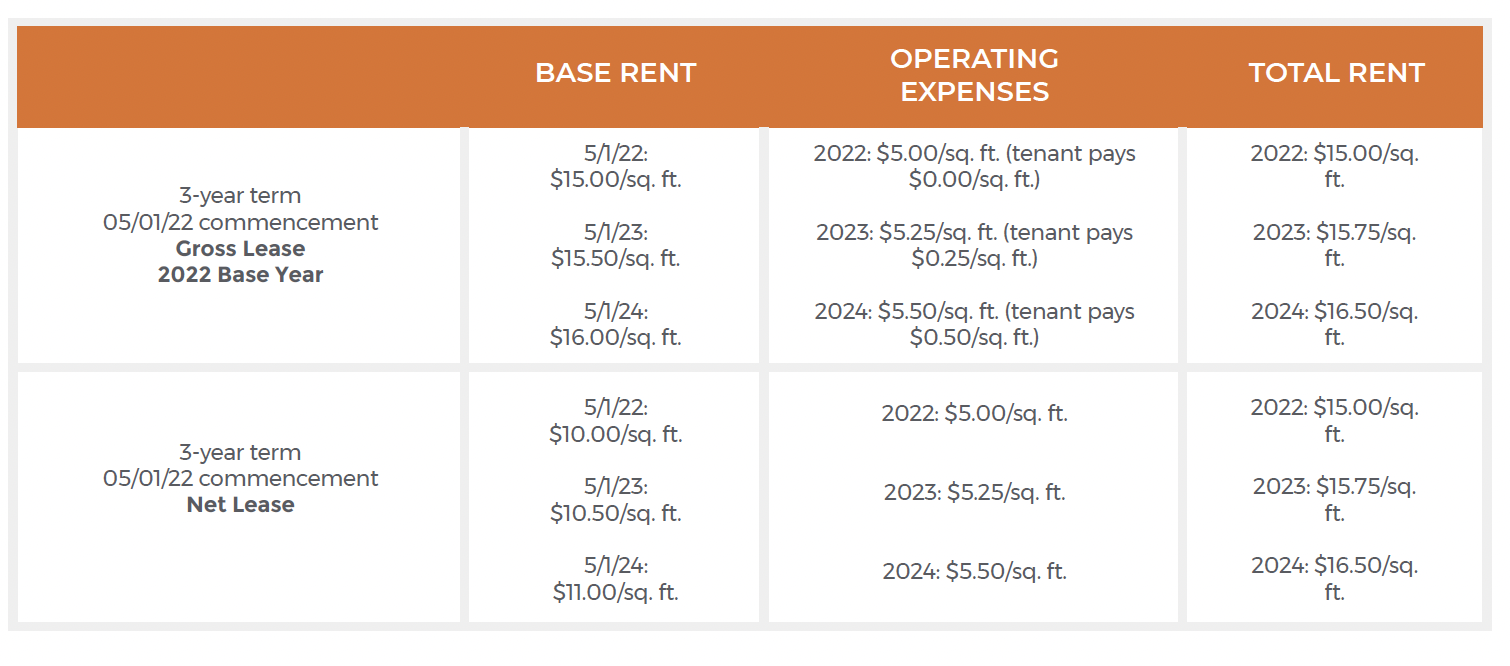

- The difference between a “Gross” and “Net” lease is typically accommodated for in the tenant’s Base Rent. Net leases will often have a lower Base Rent than a Gross lease, but in the end, the landlord will be collecting approximately the same amount.

For example:

Important Nuances In Commercial Real Estate Leases

There are some subtle but impactful nuances to watch for in both Gross and Net commercial real estate leases:

- Two different Base Year amounts: one for Operating Expenses and one for Real Estate Taxes

- Is the Base Year a calendar year or a fiscal year? This mainly comes into play for Real Estate Taxes. Operating Expenses may be based upon a calendar year while Real Estate Taxes are based on the Fiscal Year of the taxing authority.

- Will Base Rent be reduced if operating expenses for a particular year fall below the Base Year? Certain items can be excluded from the Base Year only. Most likely, these would be items that are considered “unusual” and not normally incurred as part of the normal operating/maintenance of the building.

Leases usually allow the landlord to include the amortization of certain capital expenditures over the useful life of the project or equipment being amortized. However, some leases allow for the exclusion of this amortization from the Base Year. To illustrate why this is done:

- Imagine a large capital project completed in 2021 with a useful life of 5 years.

- The amortization schedule for the project reflects $10,000 annually for years 2021‐2026.

- No further amounts can be included in Operating Expenses on this project after 2026.

- A tenant moves in and has a Base Year of 2026. When determining the tenant’s Base Year expenses, the $10,000 of amortization expense is included.

- In 2027, the amortization of this project drops off, but the tenant’s base year is inflated by $10,000, thus lowering the amount of expenses that the landlord can collect.

- By adding language to the lease, excluding amortization from the Base Year, the landlord protects itself from under‐collecting due to artificially inflated Base Year stops.

For Base Year gross leases, make note of the landlord’s ability to adjust the Base Year in the event real estate taxes are re‐assessed.

- Oftentimes it takes two or more years to contest a real estate tax assessment, but the tenant and landlord cannot wait this long to set a Base Year and begin operating expense reimbursements. When the final decision is made by the taxing authority, the result is often a reduction in real estate taxes.

- Some leases allow the landlord to go back, reduce the Base Year and recalculate any operating expense amounts that were already determined in prior years. The tenant would then owe the landlord additional sums for prior years.

- The landlord is allowed to do this because the reduction in real estate taxes will ultimately reduce taxes for all years going forward. If the Base Year is over‐inflated, the landlord will not collect the appropriate amount of reimbursements to cover the tax expenses for current years, so the Base Year needs to be adjusted proportionately.

Those are the essential basics on Gross and Net Leases. We hope you found this post to be helpful and educational. If you’d like to learn more about commercial real estate leases in general, there’s a comprehensive primer on leases called “The ABCs of Commercial Real Estate Leases” in the Library section of our web site. In addition, there’s a glossary of commercial real estate lease terms that has definitions to over 140 lease terms, from the common to the obscure.

By Terry Banike, Marketing Manager, Realogic