How Pro Sports Teams Have Become Big Players in Commercial Real Estate

Welcome to Part 4 in our series on stadium anchored mixed-use development, a concept that is completely transforming professional sports, sports stadiums and arenas and commercial real estate.

In Part 1, we discussed our hometown Chicago Bears’ quest to build a new, state-of-the-art stadium and adjacent mixed-use district, a story that has taken many unexpected twists and turns over the past year.

In Part 2, we examined the business side of professional sports, a massive, $179 billion industry in North America, including where pro teams’ revenue comes from and the factors that have been driving the stadium and arena development and renovation boom that began in the late 90s and continues today.

In this installment, we discuss how and why the traditional stadium finance and revenue models prevalent in professional sports for many decades evolved, the first major league sports franchises to embrace the stadium anchored development model and how MLB’s Atlanta Braves ground-breaking stadium anchored commercial real estate district paid big dividends on and off the baseball field.

The Atlanta Braves’ Ambitious Plan For a Stadium Anchored Real Estate District

In January 2014, Braves Development Co, a real estate development company owned by MLB’s Atlanta Braves, finalized the purchase of a 57-acre plot of undeveloped land in Cobb County, GA, just outside downtown Atlanta. Just four months later, in April, the team announced it was purchasing an additional 25 acres nearby. The acquisition of the land was the initial step in an ambitious and trailblazing initiative by the baseball team that would help usher in sweeping changes to professional sports and commercial real estate.

An Outdated Stadium Needing Expensive Upgrades

Since 1997, the Braves had called Turner Field near downtown Atlanta home. Formerly named Centennial Olympic Stadium, the venue was originally built for the 1996 Summer Olympic games and boasted 85,000 seats.

So the stadium would not sit idle and unused once the Olympics were over, it was planned and designed in such a way that it could eventually be converted into a baseball stadium for the hometown Atlanta Braves. Various Olympic sponsors and the TV network NBC, which televised the 1996 Olympic games, paid for most of the stadium’s construction costs.

After the conclusion of the 1996 Summer Paralympics, the north wall was removed and the cavernous stadium, which hosted the games’ opening and closing ceremonies and track and field events, was converted into a 49,000-seat baseball park for the Braves. The Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games, the organization that led the city’s pitch for and presentation of the games, paid for the baseball retrofit. The Braves leased Turner Field, named after former team owner and local media magnate Ted Turner, from the Atlanta Fulton County Recreation Authority, the public entity that owned it.

Although Turner Field was still relatively new by stadium standards, by the early 2010s the team believed it had become outdated and estimated it needed upwards of $150 million in structural renovations, plus another $200 million in new fan amenities, to bring it up to date.

The Old Sports Stadium Model

Also, Turner Field followed the traditional sports stadium model that had prevailed for decades. It was in a relatively low-income neighborhood in downtown Atlanta and surrounded by a sea of parking lots. Other than hosting 81 Braves’ home games and the occasional concert or special event, the stadium, its concession and souvenir stands and its vast sea of parking lots sat empty most days, not generating precious revenue for the team or sales tax revenue for Fulton County or the City of Atlanta. The team had tried to acquire land around the stadium to develop a mixed-use district, but to no avail.

In 2013, much to the chagrin of the city and all those who had played a role in the planning, financing and conversion of the stadium just 20 years before, Liberty Media, who owned the Braves, announced that rather than upgrade Turner Field, they would build a new stadium as well as a surrounding mixed-use district in nearby Cobb County, GA, pack up their uniforms and equipment and move to the suburbs. The new stadium anchored real estate district was to include office, retail, hospitality and entertainment space, a hotel and apartments.

A New Sports Revenue and Stadium Financing Model

Rather than overseeing financing and construction of the stadium and leaving the development of the surrounding real estate to outside developers and investors, as had traditionally been the case for pro sports teams, the Braves organization planned on doing something that had been novel to that point: developing the commercial real estate district too with various partners and maintaining an ownership share of the property, giving the organization control over the project and, more importantly, as landlord of all that prime, optimally located mixed-use real estate, opening up a whole new revenue stream for the team.

The Atlanta Braves Partner With Commercial Real Estate Developers

The Braves’ development group partnered with several prominent Atlanta-area developers on the project. Pope & Land Enterprises developed the office component; Pollack Shores the apartments; and Fuqua Development the retail component. Commercial real estate services firm JLL served as project manager.

The Braves’ Stadium Anchored District Becomes a Public-Private Partnership

Cobb County agreed to contribute $300 million towards the project, or 45% of the cost of the ballpark. The funds were to come from the reallocation of various tax and bond revenues and new taxes and surcharges, including on rental cars and hotel rooms. The agreement to help fund the stadium and surrounding development was controversial because the county made the decision without holding a public referendum. The Braves organization and their development partners contributed an additional $372 million towards the project, for a total tab of $672 million.

The First Sports Anchored Mixed-Use Real Estate Districts

The Atlanta Braves were not the first pro sports team to get into the commercial real estate game. That honor unofficially belongs to the NFL’s New England Patriots, who back in 2007 broke ground on the 1.3 million square foot Patriot Place, a retail, restaurant and entertainment district near the team’s Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, MA.

Around the same time, another NFL team, the Green Bay Packers, began acquiring land adjacent to its stadium, Lambeau Field, to develop Titletown, a 45-acre mixed-use district that includes retail, restaurants, bars, apartments, townhomes, hotels and office space.

MLB’s St. Louis Cardinals began planning Ballpark Village, an entertainment district adjacent to their Busch Stadium in the late 1990s, but the first phase didn’t open until 2014 and it consisted of a single 150K sf building that primarily housed bars and restaurants and was home to the Cardinals’ Hall of Fame.

And, while a number of sports stadiums were surrounded by bars, restaurants, retail and apartments, including Chicago’s venerable Wrigley Field and Boston’s iconic Fenway Park, that development had mostly occurred organically and was not spearheaded by the team nor was all of the surrounding real estate owned and operated by the team.

A New Frontier for Professional Sports and Commercial Real Estate

At the time, however, the Braves’ plan for a sprawling stadium anchored mixed-use district was the largest and most ambitious the sports world had seen, one that pro sports franchises around the world were watching keenly. That’s because the Braves’ plan was a response to many of the business and financial pressures professional sports teams were experiencing at the time– and are still experiencing today– and other teams hoped the strategy might help them with their own stadium and revenue challenges.

The age, location and configuration of the Braves’ old home, Turner Field, limited the amount of revenue the stadium could generate for the team without it undergoing significant and costly renovations, stadium revenue being sports teams’ second biggest revenue stream and one of the few sources of revenue MLB teams don’t have to share. In addition, providing a state-of-the-art stadium experience had become essential for teams that were competing against TV and streaming services, which were growing ever more prevalent and sophisticated, for fans’ attention and dollars.

While the Braves coveted a new stadium, the traditional model of using tax free municipal bonds to finance it was not an option in this case, partly because the city had recently agreed to help finance a new stadium for the NFL’s Atlanta Falcons.

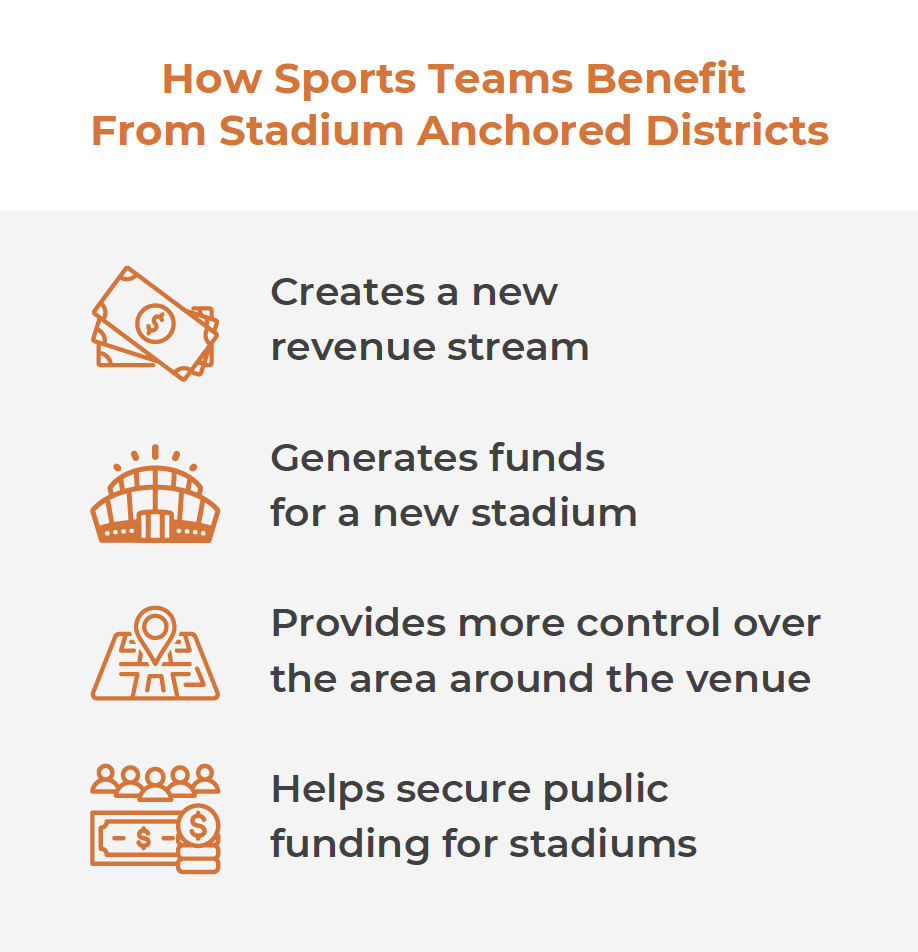

So, like many professional sports teams in the same position, the Braves were essentially forced to reconsider their traditional stadium finance and revenue models and look for new, non-traditional strategies. One that seemed to check all the boxes was to take the lead in developing the real estate around the stadium rather than leaving it to third parties and maintain an ownership stake in it, becoming a commercial real estate landlord.

The Dividends of Becoming Commercial Real Estate Developers and Owners

In the past, whenever pro sports teams lobbied cities and states to fund new stadiums, their pitch usually centered on the premise that the presence of a new stadium would generate enough economic lift and real estate development in the surrounding area to cover the cost of the stadium’s financing, but studies showed that was rarely the case and taxpayers were usually left holding the bag. As a result, the local and state government groups that made the decisions on public financing had become more resistant to the idea.

But, teams found that by putting some skin into the game and committing to developing and owning the real estate surrounding the stadium themselves rather than leaving that to someone else, local governments were more agreeable to helping with financing because they were more confident the new real estate would generate additional sales and property tax revenue to cover the costs – usually tax-free municipal bonds– and then some.

Also, by maintaining full or partial ownership of the surrounding real estate, the team could use the revenue from tenant rents to help pay for the new stadium. This reduced the amount of debt they needed to take on for the project or the amount of cash they needed to contribute, helping teams maintain a healthy balance sheet. In addition, it reduced the amount of public financing teams needed to request, further improving the chances of getting approval from the local and state governments that controlled the purse strings.

More Control Over the Area Surrounding the Stadium

Developing the surrounding district itself instead of leaving it to third-party developers —or at least being heavily involved in the development process, including planning and design— gives sports franchises more control over the look, feel and layout of the district as well as the tenant mix, so they can help ensure the adjacent real estate enhances the stadium, contributes positively to fans’ game day experience and reflects well upon the team’s brand.

A New Revenue Stream For Pro Sports Teams

Then, there was perhaps the biggest benefit of all to developing and owning the commercial real estate surrounding the stadium: a new, long-term revenue stream for the team, one that wasn’t limited by the physical or technological constraints of the stadium or that had to be shared with other teams– a highly valuable asset that generated revenue year round, day in day out, even on days games weren’t being played at the stadium or arena or concerts or special events weren’t taking place.

Next, The Atlanta Braves Knock It Out of the Park

In the next post in our series on stadium anchored mixed-use development, we’ll look at how the Braves’ new baseball stadium and adjacent mixed-use development impacted the team on and off the playing field, the impact on Cobb County and how the concept’s success inspired other professional sports teams to pursue their own stadium anchored real estate projects.

On a related note, if you happen to be involved in sports anchored development, Realogic offers several services and solutions that can help you maximize the returns on your next project:

- Our off-the-shelf Excel development models have been tested and refined over the course of 30 years and thousands of successful and profitable commercial real estate projects and can be used to accurately model even the biggest and most complex mixed-use projects. Using Realogic’s accurate, proven models instead of taking on the formidable task of building your own will save you time and money, eliminate the trial and error and give you greater confidence in your numbers.

- Or, if you’d prefer, we can do the financial modeling for you. Realogic’s skilled, experienced consulting team has modeled thousands of commercial real estate projects of all types and complexity over the past 30 years, including ground-up development and mixed-use properties. We work quickly and accurately and can work in your choice of modeling platforms. Another big benefit: our transparent financial models feature exposed formulas so you can see exactly how numbers were calculated and make modifications and adjustments as you see fit.

- Finally, if your sports anchored project is located in a Qualified Opportunity Zone, as many are, we have extensive experience working with QOZs and QOFs. We know how to deftly navigate the ins and outs of Opportunity Zones and offer a variety of expert services and solutions to help you maximize the return on your Opportunity Zone investments.

About the Author

Terry Banike is Vice President of Marketing for Realogic. Over the course of his career, he has worked in marketing, communications, journalism and public relations, and has written news stories and features for newspapers, trade publications, newsletters and blogs. A rabid reader of anything and everything on commercial real estate, Terry closely follows commercial real estate news and trends and frequently posts about real estate on the Realogic Blog. He can be reached at tbanike@realogicinc.com.